The

Silver Centenary - Western Australia's Oldest Aircraft

by

Mervyn Prime

Western Australia's oldest existing aircraft was built to commemorate the State's centenary in 1929, and was constructed from chalk drawings sketched on the floor of a country town powerhouse.

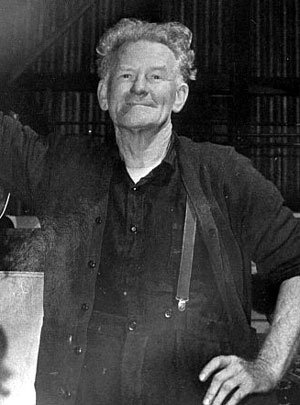

The

builder, Selby Ford, was born in Perth in 1900, but lived most of his life in

the wheatbelt town of Beverley, some 100 km south east of the W.A. capital. His

interest in flying can probably be traced back to 1919 when one of Major Norman

Brearley's aircraft visited the town, carrying out joy flights. Young Selby Ford

went up for a flight, and from this time he had a driving ambition to build an

aircraft of his own.

From

his chalk drawings Ford made up templates which he then turned into components

using spruce and maple timbers. Ford also interested the local butcher, Tom Shackles,

in his project and he too became an enthusiastic partner in the venture. Tom's

sister Elsie also became involved and she ended up undertaking all the fabric

and sewing work for the machine, which by then was taking shape on the floor of

the Beverley powerhouse. Work continued on the aircraft into 1929 and an Australia-wide

search was then undertaken for a suitable engine for the machine, but without

much success. By a stroke of good fortune, the 1929 Centenary East-West Air Race

was then in full swing and one of the aircraft crashed at Baandee, some 120 km

north east of Beverley. This proved to be Ford's salvation as a virtually undamaged

engine "fell from the skies" and into his lap. He hurried off to Baandee

and purchased the engine for £170.

The

incident also brought his work on the aircraft to the attention of the authorities,

as a small item on his purchase appeared in a Sydney newspaper. The Civil

Aviation Branch (CAB) immediately despatched their W.A. inspector, Jim Collopy,

to Beverley to talk to Ford and to examine the almost completed machine. Collopy

had this to say in his report to head office:

"Ford and Shackles have

had no aircraft experience, and their knowledge of aerodynamics and aircraft design

is very limited, and taking this into account they have made a very good effort.

The building of the machine was so far advanced that a detailed inspection of

every component and assembly was practically impossible, as there was not a single

sketch, drawing or diagram to assist one in the inspection of assemblies already

built up."

This lack of drawings was to prove fatal to the future of the project, as later events would show.

Collopy indicated to Ford what was necessary to have the machine registered, and also recommended that a sturdier undercarriage be fitted. After making the recommended modifications, Ford then applied to have the aircraft registered and, being confident that this was only a formality, painted the start of registration G-AU.. on the fuselage. (At that time Australian aircraft were still registered under British marks, and the Australian prefix of VH was not applicable.)

In early June 1930 Ford wrote to the Department advising that his aircraft would be ready for its first test flight in a few weeks time and that Capt. C.H. Nesbitt of Western Air Services had agreed to pilot the machine.

At dawn on Tuesday July 1st 1930 the front wall of the powerhouse was demolished and the Silver Centenary - so named because of the machine's striking silver and blue colour scheme, and as it had been built during W.A.'s Centenary celebrations the year before - was rolled outside. The machine was then towed along Beverley's main street to Benson's paddock, about a kilometre away. There were mixed feelings among the townspeople about the proposed flight: schoolchildren had been given the day off to watch the flight, but the local Shire Council were firmly against the flight as they claimed that Selby Ford had no right to risk his life, and thus leave the town without a powerhouse operator!

At Benson's paddock Capt. Nesbitt climbed aboard the gleaming silver bird, started the motor and within seconds was in the air. He said later that he had intended to taxi up and down the paddock several times before attempting the flight, but once he got into the cockpit the "feel" of the aircraft was just right so he decided to "give it the gun." After a 25 minute maiden flight Nesbitt made a circuit over the growing crowd and landed back in the paddock. In turn, he then gave Ford, Shackles, and their respective sisters Rita Ford and Elsie Shackles a 10 minute joyflight each.

On July 4th Nesbitt and Ford left in the Silver Centenary for Northam, about 70 km to the north, where they intended to rendezvous with Amy Johnson and Major de Havilland, who were flying in from interstate, and escort them to Perth. Unfortunately Amy was delayed in Kalgoorlie, so Nesbitt and Ford flew on to Maylands (Perth's airport at the time) and received a tumultuous welcome. West Australian Airways made a hangar available for the aircraft and shortly afterwards Amy arrived and inspected the homebuilt machine. She expressed sincere disappointment that bad weather prevented her from taking it up for a spin.

The aircraft flew back to Beverley on July 14th and, ironically, the next day the Beverley Council expressed its heartiest congratulations to Ford and indicated a willingness to assist him with any future ceremonies.

Capt. Nesbitt left Perth on October 4th 1930 in his Puss Moth aircraft, en-route to Beverley where he intended to demonstrate the Silver Centenary at the local showgrounds. Unfortunately his Puss Moth crashed and Nesbitt was killed. The Silver Centenary was not to fly again until April 1931 when some ten flights were undertaken - mostly with pilot Warren Penny at the controls - with the last flight being made to Maylands. Penny became apprehensive about the lack of registration letters on the aircraft and wrote to the Controller of Civil Aviation, enquiring whether it was in order for him to fly the aircraft.

The reply came back to the effect that the aircraft was only licensed in the experimental category, and hence flights should be restricted to a radius of 5 km of the Beverley airstrip. Through some misunderstanding it seems this was never explained to Ford. He then sought approval, which was granted, to have the machine flown back to Beverley by Capt. F. S. Briggs of the Shell Company on September 20th 1931.

Ford then sought clarification from the CAB as to the requirements to have his aircraft added to the civil Register. He was told that full diagrams, stress charts and the like would have to be submitted - none of which he had.

In December 1931 approval was given to the Vacuum Oil Company to display the aircraft at the Narrogin Aerial Pageant, conditional upon the machine being flown solo to Narrogin and not flown at the Pageant itself. The 140 minute round trip was flown on December 5th and 6th 1931 and would prove to be the last time the machine took to the air. Although the aircraft's log book showed it only made 21 flights, and was in the air for only 9 hours and 40 minutes, these figures must be viewed with some skepticism as several of the aircraft's well publicised flights were not recorded in the log.

Ford and Shackles continued to seek to have the machine's experimental licence upgraded to a full certificate of registration, but to no avail - the problem still being a lack of suitable drawings.

In July 1932 pilot George Lewis, later to gain fame as the operator of Goldfields Airways, wrote to the CAB seeking to use the Silver Centenary on a series of survey flights in rugged country north of Kalgoorlie. He estimated the flights, to locate likely gold bearing areas, would take in the vicinity of 20 flying hours and he intended to fit an auxiliary 54 litre fuel tank in the front seat to increase the machine's endurance. Lewis also indicated that he would wear a parachute in case of emergency! He also told the CAB that his hire of the aircraft was to enable the builders to recoup some of their construction costs. Needless to say, in view of the aircraft's experimental license status the application was refused.

In view of his inability to supply the CAB with the drawings they required, Ford returned the Silver Centenary to the Beverley powerhouse in 1933, and it remained there until his death in a road accident on July 15th 1963. The previous year the Western Australian Museum in Perth had expressed an interest in displaying the aircraft but, following his death, the townspeople of Beverley started a Selby Ford Memorial Fund with the intention of keeping the machine in their town.

Ford's sons, Brian and Graham, emulated their father on January 6th 1964 by demolishing the wall of the old Beverley powerhouse and rolling the aircraft out into the sunshine for publicity pictures. Over the next few months the aircraft was cleaned up and refurbished prior to being placed in temporary storage pending the completion of the Beverley Aeronautical Museum in 1967. The building was the result of the townspeople's donations into the Memorial Fund and some Government funds.

Back

to the main Items of General Interest

index

Back to the main Airworthiness index

Back to the main Western Australia index

If

this page appears without a menu bar at top and left, click

here